With businesses under pressure and budgets even more so, deciding who to develop and progress has never been more challenging, more important or under such financial scrutiny. HR departments are responsible for delivering focussed and accountable training programmes, creating up-to-date succession plans and managing talent pools, and are increasingly being asked to deliver more and to do so more quickly and for less money.

Feedback is a very powerful and surprisingly cost effective means to assess and develop individuals, teams and the business as a whole. Cost effective ‘talent’ tools are now available for organisations of all sizes and the wider benefits can be accrued without the need for full-blown enterprise systems. Used effectively, these tools allow employees to receive structured and meaningful feedback on their performance, construct focussed training plans and work experience opportunities and set realistic career aspirations. For the organisation, collating results can help inform the overall skills development plan, training and succession plans. This article examines the role and contribution that feedback can make to the development of both individual and organisational capability.

Without feedback the individual is left in the dark as to the impact of their decisions and actions on their organisation and relationships – it is the key to self-insight. Feedback comes from a number of structured and unstructured sources, including objective sources such as financial, business process or HR data (employee turnover, for instance) and subjective sources such as comments or ratings from managers, peers or customers. Senior staff often fear receiving feedback because of its connection and potential threat to their self-identity. However, feedback can of course contain both positive and negative elements and is increasingly being sought and used for more than just raising self-awareness.

Gathering and reporting feedback

In addition to soliciting feedback for personal learning and development planning, common drivers for embarking on a feedback programme include the HR processes of:

- selection for progression and promotion

- performance appraisal

- streaming for leadership and management development programmes

These feedback programmes are the accumulation of structured and unstructured feedback (generally using a questionnaire as a diagnostic) from colleagues who work with and around the individual, hence the terms ‘360° reviews’ or, in the US, ‘multi-rater feedback’ often used to describe them. When compared to other evaluation methods, such as assessments centres, gathering feedback from those with whom an individual works can be extremely cost-effective.

The output of a 360° review is typically a personal report that collates feedback from these sources into a single document for the individual. An analysis of the report highlights key strengths and development areas, often signposting development solutions available. The value of such a report comes from the actions taken as a result of its exploration. It is best practice (though sadly not universally applied practice) for a trusted person to assist an individual to interpret the data, frame the feedback that suits their own outlook and identify the development solutions that can contribute to the individual’s overall development plan.

Providing effective feedback

As managers, HR and psychology professionals, we should be used to giving feedback on a regular basis and are often asked to act as feedback facilitators, helping individuals to understand and make use of their 360°feedback reports. We may also find that we are asked to provide feedback to people on issues that others may shy away from, or to people who have proved to be particularly challenging. In these instances, as in all situations where you need to provide feedback to someone else, this simple FEED model can help ensure you make a useful contribution:

- FACTS

Describe what it is that the person actually does – what does the behaviour look like? What did they say? - EXAMPLE

Give a recent example or instance where this was important. - EFFECT

What effect does this have (on others’ perceptions, on the individual’s work, on you, on the team, on clients)? - DIFFERENT

Suggest an alternative approach – or ask the individual what they could have done differently. This model can be applied to any form of feedback and should certainly be a central consideration when designing and implementing 360° programmes.

Reacting to feedback

How we respond to positive and negative feedback depends very much on how we are wired. Those driven to succeed and attain goals (‘positively wired’) interpret and internalise positive and negative feedback very differently from those more concerned with avoiding failure and punishment (‘negatively wired’). For example, a highly motivated goal-driven employee will take positive feedback as a validation and reinforcement of current behaviour. This creates a virtuous cycle whereby the individual tends to strive harder. Negative feedback does not tend to alter much for these individuals, unless attention is drawn to it with clear consequences. The reverse is true of those who fear failure – negative feedback spurs them on to try harder while positive feedback tends not to have much impact on their motivation levels. They often feel that they have ‘escaped’ any retribution they feared. Feedback, when received by individuals without guidance or assistance from an experienced coach or facilitator, will therefore solely act to reinforce current behaviours (some desirable, some less so) and have very little impact other than maintaining the status quo or exacerbating matters: we have all witnessed highly successful people derail themselves through a lack of awareness of the downsides to their behaviours. Although some people are averse to feedback, others welcome it, but seeking feedback can be a risky business.

Negative Feedback

Positive Feedback

‘Negatively wired’

Ouch – That hurt! I’d better try harder so it can’t happen again

Phew – avoided failing, done enough, no need to try harder.

‘Positively wired’

What? There must be some mistake, so no change to present course!

I’m good, oh Yes! I can carry on carrying-on!

For individuals who are offered no support, negative peer reactions can add to the psychological cost of seeking feedback. Those with a positive feedback orientation (that is, they seek it out and like receiving it) recognise how helpful it can be, tending to be both resilient and sensitive to how others see them. They also feel responsible for taking action for their own growth and development based on the feedback. These people are also often described as ‘continuous learners’.

So, whilst it is generally accepted that feedback is essential for the learning process, for a number of reasons many of us still find it difficult to respond constructively, particularly to feedback which is perceived as being negative. Conversely, some people feel uncomfortable when offered praise. This is where well thought-out and carefully constructed feedback (as described in the previous section) can help overcome less-than-enthusiastic responses to performance or behaviour reviews. Some people are naturally more receptive to feedback than others, but timing also plays a crucial role in ensuring a positive response. While there are no hard and fast rules, the following guidelines can be useful:

When to offer feedback

- When the individual has asked for it

- Shortly after the individual has gone through a 360° review process, assessment or development centre

- Soon after a critical event in which the individual has either performed particularly well or could have done better

- When the individual seems unaware of an issue which is impacting on their performance or limiting their chances of progression

- When the individual’s performance or behaviour is affecting others

- During coaching sessions or informal discussions of the individual’s performance

When not to offer feedback

- I When the individual is not ready to hear it (if they are very upset or angry, for example)

- When there are distractions or other people around (particularly if the feedback is of a critical nature)

- When you don’t have enough information to give meaningful feedback

- When an individual has been given sufficient feedback already, but is avoiding taking responsibility for doing something about it

- When the individual is showing signs of resistance to the wider development programme

Overcoming resistance and defence mechanisms

Suzanne Skiffington and Perry Zeus in their book Behavioural Coaching highlight the importance of understanding defence mechanisms when providing feedback. They cite the example of someone who claims to love receiving feedback, both positive and negative, but is actually just defending themselves against rejection or hurt. Most of us feel some discomfort when being given bad news and it is important for both the feedback provider and recipient to acknowledge this when discussing performance. The job of the feedback provider is to be sensitive and alert to the recipient’s feelings and reactions, and the recipient needs to be as open-minded as possible: everyone’s perceptions can be different and the differing viewpoints of others are valuable, even if they don’t always match with our own.

When in a situation in which you are required to give feedback, it is also worth reminding yourself that few people are wholly comfortable with doing so but, with practice, preparation and some guidelines to follow, the experience does not have to be an unpleasant one for either you or the recipient.

The role of technology

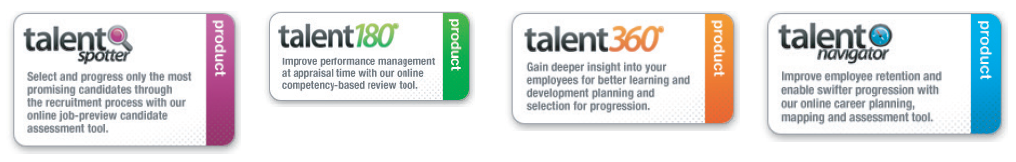

Technology has an important role to play in both managing the feedback provision process and in helping to identify ways in which people can act on their feedback. A set of development options carefully aligned with the requirements of the individual’s role can be a key pillar of support following a feedback cycle and these development options are often found within Learning Management Systems (LMSs) or within newly emerging career planning tools.

There is a very clear and direct association between using feedback and diagnostic tools and the ability of an organisation to provide much needed focus and clarity around how to spend scarce development resources. When used effectively across an organisation, feedback tools such as 180° appraisals and 360° reviews, together with career planning tools, can not only provide a rich source of feedback and a basis for constructive dialogue between a line manager and staff member, they can also provide valuable insights for the overall skills portfolio, training plan and succession planning process.

Larger organisations have had the benefits of fully integrated HR systems available to them for some time yet still often do not take full advantage of them. As the trend towards a more integrated approach to HR, training, recruitment, succession and so on (often called talent management) takes hold, the tools are more likely to be used to their full extent. However, for small and medium-sized organisations, the challenges have been greater. Many have dipped their toes in the LMS water as well as 180° and 360° feedback but these programmes are often based on laborious manual systems and, most disappointingly, not used effectively as feedback mechanisms for staff and the organisation as a whole.

Developing a forward vision

Performance improvement as a result of feedback programmes is invariably reliant on the skills of the manager and, sadly, the manager’s development is often overlooked in the rollout of such systems and processes. The manager and employee have access to and an understanding of the progression opportunities within the organisation. Internal job boards make some in-roads but fail to assist employees to set any direction for themselves (or to put their development into any context), other than that indicated by the current crop of vacancies. Career planning tools go way beyond the posting of current vacancies on the intranet by providing an open view of the skills and experience requirements for all roles in the organisation. Such transparency enables employees to evaluate their skills against potential new roles and, with the appropriate support and guidance from their line manager and the Learning and Development team, to plan a personal development pathway set within a framework of realistic expectations on all sides.

The contribution of Learning and Development

In the integrated talent management world, the role of training manager takes on a new meaning and an altogether more interesting perspective. The key to success is a sound understanding of where the business is going strategically and then interpreting the business strategy into skill requirements. From there, the training manager must utilise HR processes to ensure that the appropriate skills are recruited, trained and developed and that sufficient skills and experience are built up internally for the future and fed into the succession planning process.

Positioned correctly, this places Learning and Development as an added value function, a key part of HR and an essential contributor to the future competitiveness of the organisation.

Head Light Communications’ portfolio of Talent® software and services are ideal for:

- Professionalising public sector organisations

- Maturing high growth and medium-sized businesses

- Pioneering divisions of large organisations

References and further reading:

Skiffington and Zeus (2003) Behavioural Coaching. McGraw-Hill.

Ian Lee-Emery

Ian’s career began in Information Technology. As a Computing Science graduate, he joined GE (USA) in research and development in 1989. A GE sponsored MBA programme, completed in 1996, guided the transition into European commercial roles. He became a Six Sigma ‘Green Belt’ leading improvements in European product performance. In 2004 and having spent 10 years working with HR professionals to help them improve how they assess and develop their people, he founded Head Light Communications.

He is a contributor to Human Capital Management magazine, the Best Practice Club and the Business Improvement Network. Ian is a Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Marketing and professionally recognised as a Chartered Marketer. In his spare time, Ian is a keen triathlete and musician.