In a previous paper, “The Sage of Paradox”, I argued that as learning professionals we need to stop thinking of learning as an event that is organised by one set of people and imposed upon another, regardless of whether that event takes place in a classroom or via the medium of e-learning. Learning is a natural consequence of living and working: work has always involved problem solving, judgement, conflict resolution and choice – these are all learning opportunities. We can experience them and move on regardless or we can reflect upon them within the context of our environment and our core principles and, as a result, produce new insights that move us forward.

In this article I intend to take a closer look at how we can increase the impact of learning by interleaving it more closely with the world of work.

To make a difference with our learning initiatives we should think less about content and more about environment.

Informal learning

There now appears to be an upsurge of interest in ‘Informal Learning’. Indeed it would appear that this is the fashionable thing to build into one’s learning programmes. But make no mistake: to really embrace informal learning we will need to abandon some very well embedded paradigms, and the nature of paradigms is that we are often blissfully unaware that we are locked inside one.

The nature of informal learning

Research shows that around 75% of what we know, the stuff that really makes a difference to how we perform, is learned through serendipitous interactions in the workplace rather than being a result of formal, designed efforts to train people.

Before we explore the consequences of this statistic we should focus in on just one word from the above: ‘know’. What is it that we know?

Back in the 1950s the respected philosopher Michael Polyani introduced the idea that knowledge comes in two forms: explicit and tacit. Explicit knowledge comes in the form of know what, where, who, when or that. By contrast tacit knowledge is about know how, what if, know why and care why. Put simply, explicit knowledge is stuff that we know that we know and can write down, where as tacit knowledge is stuff that we use but are not consciously aware that we are using it and probably couldn’t explain to someone else how we did what we did or why we leapt to the conclusion that we did. When we operate in the tacit domain we are exhibiting what might be termed ‘expert’ behaviour. Interestingly, research also shows that around 70% of all knowledge that is useful in our organisations is of the tacit variety – this is because in some way we are all ‘expert’ at something.

I want to explore two paradigms, and their associated paradoxical consequences, that we unwittingly accept and which govern the way we think about learning. The first is this:

Paradigm – “experts know best” Ergo, if we want to improve the performance of a group of people, we find an expert in that domain, analyse how they perform and then design training so that everyone else can emulate the performance.

Paradox – “most of the time experts don’t use the knowledge they think they know.” Because expert behaviour is rooted in tacit knowledge, the expert often can’t explicitly state why they do what they do. Worse still, we then put another expert in the way, the training designer. These people have one real skill: they are adept at constructing events entirely out of knowledge that the expert can articulate and, as we have seen, this often has little relevance to the way that the experts behave.

A short detour along the route from novice to expert

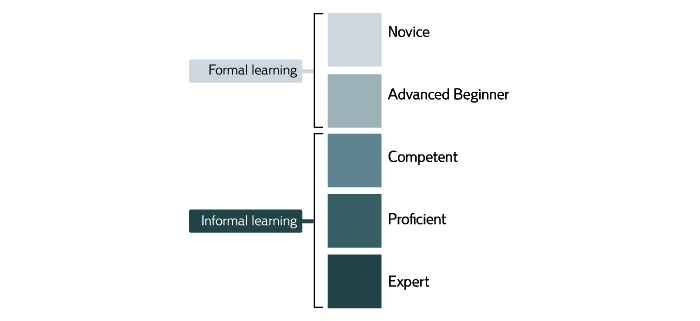

The journey from novice to expert was neatly described by Hubert Dreyfus and is captured in the diagram above. Most people can immediately identify with this journey in the context of the acquisition of a skill such as riding a bike or playing a musical instrument. To explain the importance of this insight, let’s walk through the model in the context of learning to drive a car.

The Novice driver may be taught to change gear with reference to the speedometer, hence the instruction – when you get to 10 miles per hour change into second gear. After a while, we master these simple activities and move to the stage of Advanced Beginner. At this stage we start to consider situational elements, so the speedometer may read 10 miles per hour but if the brake lights are showing on the car in front, this may not be a great time to change up. Once we have started to master these situational elements we move to the next phase, that of the Competent performer. We are now aware of the complexity of what we are doing and we start to deal with complexity by overlaying a personal plan. In driving terms, instead of going where the instructor tells us, we are involved in planning our route ahead of time – we no longer just drive around, but instead we drive with a purpose. As such, we are involved in the outcome of our activities but may still have a limited understanding of the bigger picture and be detached from decision making. In time we develop into a Proficient performer. By now we have substantial experience and start to recognise patterns of events and associate solutions that have worked before with certain patterns of events. The proficient driver will spontaneously adjust their planned route or driving style to suit emerging circumstance; we are fully involved in the bigger picture and take ownership of the outcome but still may be detached from decision making. Finally, we attain Expert behaviour. In this state the driver is no longer engaged in operating a machine but rather is fully engrossed in the driving experience. We are at one with the road; we often are unaware of what gear we are in or consciously thinking about our actions. The expert decides intuitively – we just know.

Interestingly, under conditions of extreme stress or crisis, the expert can fall back into novice or advanced beginner mode and start following rules. This is dangerous because they are neither used to or practiced at following rules. This partially explains why experts occasionally do incredibly dumb things, sometimes with catastrophic consequences.

This is the domain of informal learning.

Seasoning the Blend

The most important insight is that when we learn informally we are by and large not learning things that are or can be written down. So informal learning is not so much about content. This is crucial because we have a whole profession of training (learning) designers who are currently predominantly focused on content. Informal learning is about context, patterns and connections; these are the building blocks of judgement, intuition and wisdom. This leads us to our second paradigm and associated paradox.

Paradigm – “analysis is the only form of thinking”. Ergo the best way to understand complexity is by breaking it down into parts. So if we want to improve the performance of a group of people, we break down the activity, teach the component parts and, hey presto, when we put them back together, they will be better performers.

Paradox – “experts don’t see parts, they see wholes”.

Experts tend to think synthetically. Synthesis is the converse of analysis, so instead of taking things apart they put things together. They see wholes in the context of greater wholes. This sometimes exhibits itself in what has been termed ‘thin slicing’ – the ability to make instantaneous assessments of complex situations, assessments that can give better results than laborious analysis.

Informal learning is the process through which we store the near-infinite number of instances that will in future enable us to see patterns emerge before they do and to make connections under conditions when we only have partial data. In other words, informal learning is the process through which we acquire wisdom and judgement. It is deeply contextual, collective in nature and there are no short cuts – it takes time.

To summarise the message so far, formal learning is where we give people the building blocks to get as far as advanced beginner in performance terms. At best, all it can do is to certify that people are safe to practice. Some teams never get out of this state, or they fall back into it due to lack of leadership. Informal learning is the process by which people cycle through the journey from competent to expert, which provides real and potentially lasting leaps in performance. The journey is facilitated by being surrounded by proficient or expert performers and exposure to the full richness of context within which value is created. Total immersion in such an environment allows people to absorb the ethos of experts, start to recognise for themselves the patterns that are so obvious to the experts and, where appropriate, model the experts’ behaviour.

So as learning professionals, what can we do?

The simple answer is that most of us will just carry on doing what we do, and this is right and proper because we will always need to support the journey from Novice to Advanced Beginner. This is where the greatest cognitive load is; it is where the analytic paradigm works best and it probably accounts for 80% of the cost and effort in what we can do to make people safe to perform.

However, surely most of us would aspire to being involved in really making a difference to how people perform. To do this we must refocus our attention onto the informal learning space. We must recognise that the tools, techniques and mindset that served us so well in the traditional space are wholly inadequate to be successful at facilitating informal learning. We need another paradigm shift.

We need to move from an obsession with creating a solution towards a mindset of creating an environment within which a solution has the capacity to emerge.

Whereas formal learning (training) has learning designers, informal learning has learning architects. Let me illustrate the difference between the roles by using the metaphor of the great landscape gardeners of our past. If you visit Stourhead in Wiltshire, you may be captivated by the grandeur and beauty of what you see. You will recognise the scene because you have seen it on calendars, chocolate boxes and jigsaws. You may even feel a sense of pride that it is quintessentially English. But actually, there is nothing natural about what you see – the lakes were dug out by hand, the rolling hills were created by moving the landscape, most of the trees are not indigenous to these islands and the buildings and follies all hark back to a classical age that never really existed. Most importantly, the people who designed and built it never saw it in this form, nor could they have envisaged what it would look like today. The landscape gardener’s role is to create an environment within which beauty can emerge.

A list of necessary environmental conditions

We have seen that informal learning is the landscape within which the journey from competent to expert performance is played out. We have also seen that the landscape must be immersive, collective, holistic and challenging. What role can the learning architect play in stimulating informal learning?.

- A contextually relevant space to practise in – this is generally the workplace

- The desire and ability to cooperate productively with others – this works best when people self-select into groups

- An igniting purpose, task or vision that triggers the process of self-selection into cooperative groups

- Access to alternative and paradigms – this works best when people from disparate functions or disciplines work towards a common goal

Brian Sutton

Dr Brian Sutton is owner and managing director of Learning4Leaders. He divides his time between learning consulting assignments, writing books and acting as a visiting professor for the Institute for Work Based Learning at Middlesex University. Brian’s most recent book is 30 Key Questions that Unlock Management. He is currently working on the 2nd Edition of Teaching and Learning OnLine to be published by Routledge in early 2013.

Web – www.learning4leaders.com