A recent episode of This American Life told the story of the NUMMI car manufacturing plant in Freemont, California. In 1984, NUMMI was opened in a joint venture between General Motors (GM) and Toyota. At NUMMI, Toyota showed GM the secrets behind making, back then, some of the world’s best built and most reliable cars.

When it opened, the majority of NUMMI’s workforce were old hands from the old Freemont plant, which was considered one of GM’s worst. Employees drank on the job, were frequently absent, and even committed acts of petty sabotage.

But Toyota execs believed their system would turn bad workers into good ones. So in the spring of 1984, Toyota started flying the old GM workforce to Japan in groups of 30 to learn its system for making cars.

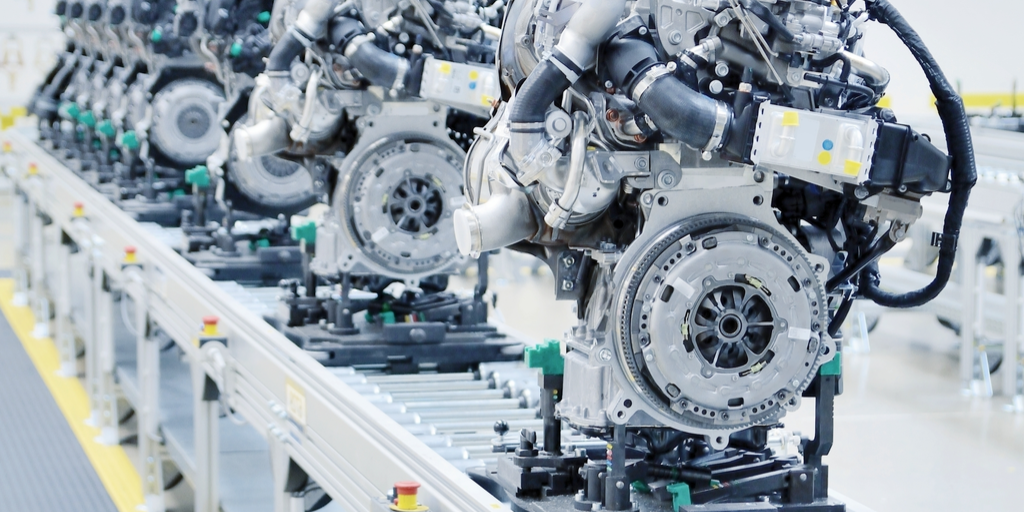

Toyota achieved its phenomenal reliability through its production system. The Toyota production system is based on the Japanese concept of Kaizen, or continuous improvement. Under the system, employees are expected to constantly look for ways to improve the production process to make their workers’ job easier and more efficient. Workers’ tasks are streamlined to the fewest possible steps, each step timed down to the second. Whenever a worker made a cost saving suggestion, they’d get a bonus.

The key to Toyota’s success was teamwork. While that now seems incredibly clichéd, to the GM workers, seeing people work together to solve problems was profound. At the Toyota plant in Japan, when someone came over to ask one of the Freemont workers if they wanted help, it was a revelation. At the GM plant, nobody would ever ask to help.

At the Toyota plant, the andon cord symbolised everything that was different about the Japanese system. This nylon rope that hung across the assembly line, and whenever it was pulled it would stop the production line so a problem could be corrected before moving along. At GM, a cardinal rule was to never stop the line. This led to a rapid accumulation of mistakes. Cars would be made with missing parts, and even engines put in backwards.

For the GM workers, learning a new way of working was a powerful, emotional experience. There was a sense of hurt pride, and a desire to compete with the production process that they saw in action in Japan. Before the first group left to go back to Freemont, they had a sushi party and the grizzled union workers from Freemont were crying and hugging their Japanese counterparts.

After just three months of the workers returning to NUMMI and implementing the system they’d learnt at Toyota, the cars coming off the line were getting near perfect quality ratings. And GM saw remarkable cost savings: one study showed that it would take around 50% more workers under the old system to build the same car.

For me, this story demonstrated the importance of social learning when it comes to continuous performance improvement, and the need for learning designers to think beyond the traditional parameters of a course. An elearning course can only ever be a jumping off point. We need to do more than pay lip service to the idea of the learner as a producer of new insights and facilitate it effectively.

Lev Vygotsky describes knowledge as something we co-construct as part of our interaction with one another. Even the most well-written, effective course won’t be as effective as what peers can teach each other. This is because the peer is so much closer to the mind-set of the learner, able to spot problems and formulate solutions instinctively.

One of the most important ways elearning can support social learning is by facilitating participation through the integration of enterprise social networking applications such as Yammer, Slack, and open source alternatives, such as Saffron Share. But social learning requires the right physical environments as well as digital platforms. Learners should always be encouraged to reflect on and discuss the training they’ve received so that they can find ways to constantly improve their processes. Like NUMMI’s kaizen method, symbolised by the andon cord, we need to create a social learning infrastructure at companies which encourages debate and facilitates unplanned collaborations. This broadens perspectives for finding better solutions, whilst enhancing performance and prompting self-reflection.

The end to the NUMMI story wasn’t a happy one. In 2009, GM declared bankruptcy and the US taxpayer bailed them out for $50 billion. One of the ironies of this was that, when GM went bankrupt, it was a better company than it had ever been.

Despite being shown a new way forward in the 80s, it took too long before the amount of workers trained at NUMMI reached a critical mass so that generational change could occur. Many commentators believe that if GM had implemented the system across the board in the late 80s they wouldn’t have gone into bankruptcy: productivity and quality would have increased so much that their loss of market share would have stopped.

To emulate the early success of NUMMI and avoid the pitfalls of GM, organisations need to mobilise their employees to teach each other and continuously improve the way in which they operate. A key way of doing this is embracing social learning.

Saffron have a new performance support tool nearing release. Interested in hearing more, or viewing a demo? Register here.